7- Polymorphism

In this last installment before we start our development project (and yes, there is a development project coming) we will talk a bit about the C++ type system, how to use it, how it ties in with object-oriented programming and how it ties in with what we’ve discussed earlier. We will see what the virtual keyword is all about, and how “a duck is a bird, is an animal” and “a table and a chair are both pieces of furniture” comes into play, and is expressed in C++. Once we’ve gone through that, you’ll be sufficiently equipped for object-oriented programming in C++.

Modeling An “Is-A” Relationship

Like I explained briefly in one of the previous installments - the one about classes - class inheritance models an “is-a” relationship. This goes a lot further than “a duck is a bird, is an animal” (therefore Duck inherits from Bird, which is derived from Animal - note that “inherits from” and “is derived from” mean the same thing): it means that whatever you can do with any animal, you can do with a duck. This is where the “minimal but complete” mantra comes in: if you have a class that models something in your application, you should make sure that you can only do things with that class that you can do with anything that “is” the same class. For example: a bottle and a basket are both containers: bottles contain liquids, baskets contain solid objects. There are things that you can do with both - e.g. carry them around, put them in a closet or on a table, etc. There are also things that you can’t do with both - e.g. fill them with liquids. If you try to fill a basket with a liquid, you’ll find that it’s very leaky and end up with a wet basket, a wet table and a wet floor. If you will the bottle with a liquid, you’ll have a full bottle. So, when designing the Container base class, you shouldn’t assume that you can put a liquid in every container.

The C++ programming language will not enforce the “is-a” relationship: you can derive a class from another class regardless of what those two classes represent. In some cases, that can be a good thing but in most cases, it’s not.

What Is And What Might Be

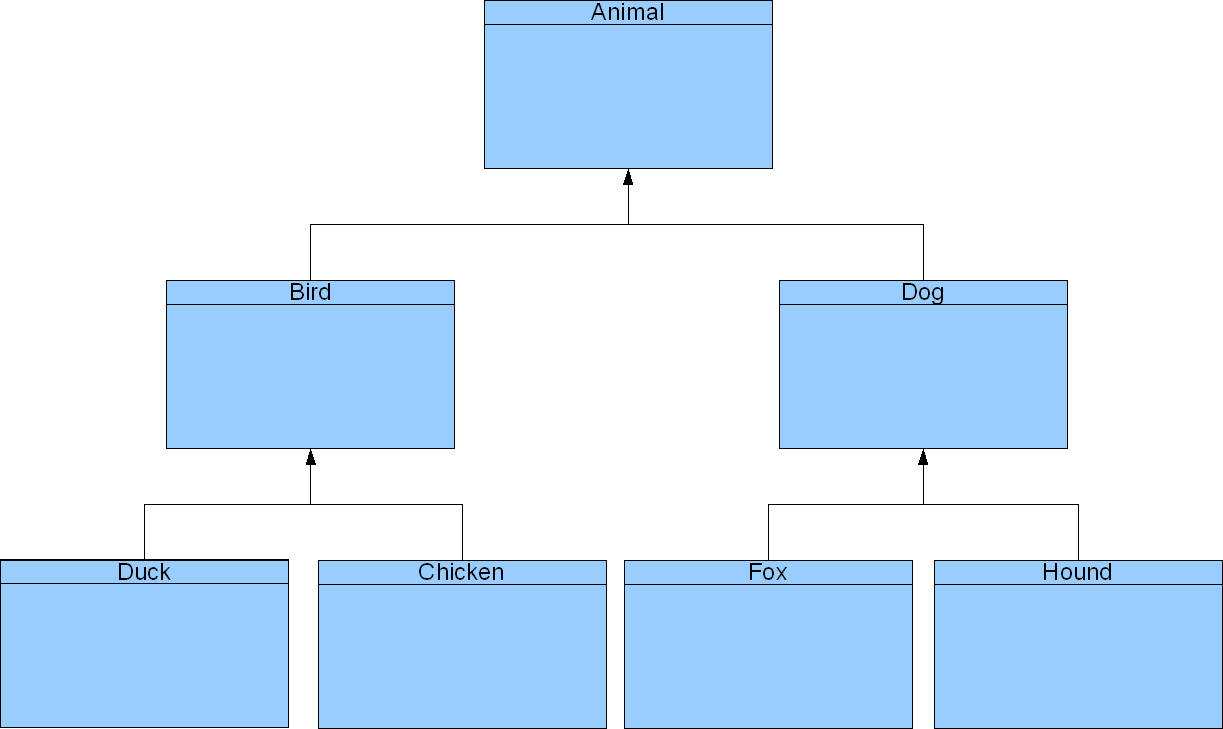

Let’s get back to our ducks, birds and animals, and make the hierarchy of classes a bit larger (this is our first UML diagram!):

I’ll leave making code out of this little class diagram up to you. You’ll note, though, that the

I’ll leave making code out of this little class diagram up to you. You’ll note, though, that the Animal class now has two derived classes: Bird and Dog and that both of them have two subclasses as well. That means that while any Duck is still a Bird, a Bird might or might not be a Duck. In the case of an Animal, you now have four possibilities: Duck, Chicken, Fox and Hound. This is the difference between what is, and what might be: for any given duck, you know that it is an animal - but for any given animal, it might or might not be a duck.

Sometimes, when writing the code, you want to treat ducks, chickens, hounds and foxes differently. I.e. you could reasonably put ducks, chickens and hounds in the same yard: the hound won’t eat the chicken or the duck, and the chicken and the duck will probably just ignore each other. If you put a fox in the same mix, however, you may have a very serious problem - although you can put a few foxes together without problems either. Let’s take a look at a bit of code:

#include <cassert>

#include <stdexcept>

#include <vector>

class Animal

{

public :

virtual ~Animal();

};

Animal::~Animal()

{ /* no-op */ }

class Bird : public Animal

{

};

class Duck : public Bird

{

};

class Chicken : public Bird

{

};

class Dog : public Animal

{

};

class Hound : public Dog

{

};

class Fox : public Dog

{

};

class Yard

{

public :

void add(const Animal * animal);

private :

std::vector< const Animal * > animals_;

bool have_fox_;

};

void Yard::add(const Animal * animal)

{

bool is_fox(dynamic_cast< const Fox* >(animal) != 0);

if (animals_.empty() || have_fox_ == is_fox)

{

animals_.push_back(animal);

have_fox_ = is_fox;

}

else

{ // uh-oh!

throw std::runtime_error("Incompatible animal!");

}

}

int main()

{

bool thrown(false);

try

{

Fox fox;

Hound hound;

Yard yard;

yard.add(&fox;);

yard.add(&hound;); // throws

}

catch (const std::runtime_error &)

{

thrown = true;

}

assert(thrown);

thrown = false;

try

{

Fox fox;

Hound hound;

Chicken chicken;

Duck duck;

Yard yard;

yard.add(&hound;);

yard.add(&duck;);

yard.add(&chicken;);

yard.add(&fox;); // throws

}

catch (const std::runtime_error &)

{

thrown = true;

}

assert(thrown);

thrown = false;

}

If we just pretend that the path to the call to add loses all track of the type of animal we’re adding for some reason, we still have the information at run-time, using Run-Time Type Information. The add function uses a dynamic_cast to find out what type of animal we have. A dynamic_cast to a pointer type returns NULL (0) if the object pointed to is not of the type cast to, or returns a valid pointer otherwise, so we can check whether our animal is a fox by using dynamic_cast< const Fox * >.

There are various other cast operators: static_cast is probably the most popular of them, and reinterpret_cast is likely to be the least popular. I’ll let you find out what other cast operators exist. All of them do the same thing, though: they coerce a pointer, reference or object into some other type. The C++ type system will automatically do that in some cases - e.g. from Fox to Animal - but won’t in other cases (e.g. from Animal to Fox).

The virtual Keyword

We’ve already run into the virtual keyword a few times now: you may have noticed that the Animal class has a virtual destructor and in the installment on classes, we added virtual methods to our base class (actually, they were even abstract), and overloaded those methods in the derived classes. If you’ve been paying attention, you might have a pretty good idea what the keyword is for: it allows you to call a method on an instance of a base class and run the version of the derived class. Thus, the move method was virtual so calling move on an animal would call the proper function on the duck (and now, the chicken, the hound or the fox, depending on the actual type of the object).

A method that is not virtual does not behave the same way: if you call a non-virtual function on a class, even if a function of the same name exists in the derived class, the function in the base class will be called. Once a method is declared virtual in a base class, it’s virtual in all the derived classes as well, so you don’t need to re-declare it virtual (though it is good practice to do so anyway).

Construction And Destruction

If you construct an instance of Duck and you give each of the classes Animal, Bird and Duck a constructor, you’ll find that the order in which they are called is Animal, followed by Bird, followed by Duck. If you give each of them a destructor, you’ll find the opposite is true for destructors: construction is done bottom-up while destruction is done top-down. Copy the code from the example and give it a try.

Conclusion

We’ve now gone through the basics of polymorphism and concluded the introductory part of this series. The next part will start us off writing a full-fledged application with a graphical user interface, threads and networking. We’ll parse XML files, work with the file system and try to make it all into something useful. I’ll leave you guessing until the next installment what the application will be.